So, if you are as all about NPR in your car as I am, you may have heard this report on the BBC world service about the Bird Flu dance that is spreading in the clubs of Abidjan, Cote D'Ivoir. On the radio you could hear snippets of the bird-flu song which was created by an artist called DJ Lewis, and it sounded hectic! So I wanted to find a link to it for this site.

Here's the problem- Although tons of sites are linking to BBC story and commenting on the phenomenon, I couldn't find one that had a link to the actual song, or better yet a video for it. This seemed strange to me and then more offensive as I went over it. All these people want to have a good cubicle chuckle about the crazy Africans, but no one wanted to hear the actual song? Like it was assumed that the song would be garbage.

This isn't the first time I've seen Ivoirian music dissed in print- in the awesome book Nine Hills to Nambonkaha, author Sarah Erdman has nothing but respect for the culture of Cote D'Ivoir, her home for two years... except the music. She describes the dance music from Abidjan as noisy repetitive casio beats and says at one point she was "desperate to get away from the screaming atari whine of the music". Casio beats? Atari whine? Sounds awesome!

I was also weirded out to see that very high up on the list of Google hits for "Bird Flu Dance" was a white power message board where someone had put up a link to story. This seemed kind of strange and ominous. If I wrote "Bird Flu Dance" on the Hollertronix message board, it wouldn't even rank. But this board, run in the same way, had big pull in the rankings. What's up with that?

Anyway, I tried to find some media relating to the Bird Flu dance, and this is what I came up with- a video of a kid showing off a completely different version of the bird flu dance! This one is based on a Jamaican dancehall song that predates the African version by several months. So, did DJ Lewis bite the bird, or was it just something in the air?

Saturday, May 27, 2006

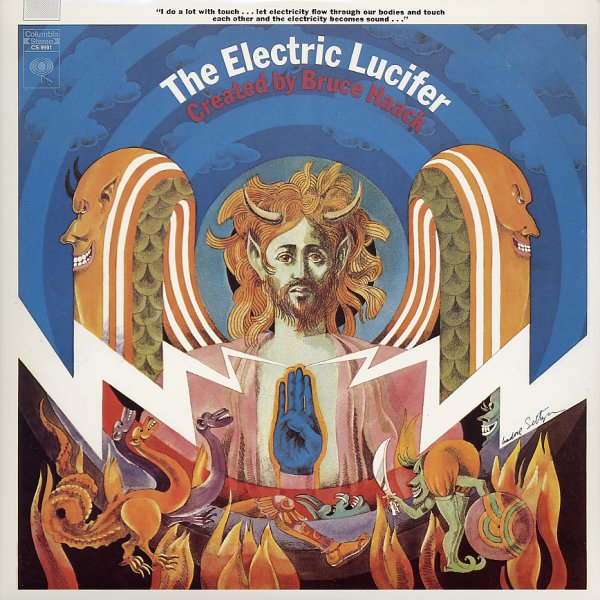

My man Sharkey from Clockcleaner gave me a copy of the album "Electric Lucifer" by Bruce Haack over a year ago but I just finally got around to listening to it last week. You have no idea how facemelting this shit is.

Released in 1970, "Electric Lucifer" was composed by Bruce Haack and performed on electronic synthesizers that he built himself out of cheap parts he bought on Canal Street. Haack is mainly known as a composer of bizarre childrens music, especially since the release of the Dimension Mix tribute album where artists such as Beck and Stereolab cover Haack songs to raise money for autism research.

While some might argue that all of Haack's music would be unsuitable for children, "Electric Lucifer" is squarely intended for adults. In fact I don't think that hardly anyone is old enough to listen to it. My girlfriend Genevieve is so terrified by the record that she won't let me play it when she's in the house.

Thats because this is extremely weird electronic psych filled with unsetlling noises and tones and all filled with acidhead messages about God, the Devil, war, technology and unicorns. And dragons. Haack studied psychology, which shows out well on tracks like "Program Me", but what can explain the rest of his lyrics, which read like the back of a bottle of Doctor Bronner's soap?

"Lucifer -- I read that after the war you and your angels were sent out of heaven to Earth. Most of us like it here but we don't believe in war. Our newborn are beginning to understand mistakes of the old ones. Maybe the Angel People will all unite. The key is Powerlove"

Basically it sounds like if Kraftwerk composed the music for an evil robot circus and got Phillip K Dick, a late-era Phillip K Dick, when he was really off his shit, to be the singing ringleader after dosing him with speedy acid and locking him in a closet with only a pen light and a bible for 4 hours.

Haack was definitely on to something, though. There's a kind of mind-blown sense of duality here that rings quite true for me. And right around the same time L Ron Hubbard was building an entire religion based on ramblings even more far-out than Haack's. Haack was also quoted many times in the 60s and 70s that in the future most music would be made by computers, and that's when he would find his fame, when music would be "shared electronically" for free, obviating the need for record companies. What you know about that?

Theres a good Bio of Haack here, but I couldn't track down any Mp3s for you. Best to get a copy of the whole album to listen in sequence to hear the "story" unfold.

Monday, May 01, 2006

Trap Door is a new "international mystery pysch mix" on Dis-joint records. I'm not sure what the legalities or moral issues are with reprinting all this shit without credit, but hey, hot fire is hot fire. And I do deem it to be so after listening to the sound samples here.

I myself have a potential "South American Mystery pysch mix" to be made once I get all this wax I've bought down here on the plane. Which will be in exactly 48 hours. Contact White Animal to pre-order your copy now.

WHITE ANIMAL BOOK REPORT

In my dwindling last days of leisure in Bolivia I polished off two books while sitting by lake Titikaka that I figured were worth mentioning. Both of these books came from a gringo book swap in Copacabana, and both of them came with summary blurbs that would normally frighten me off. They were, respectively, something like:

"A young married couple struggles with the soul-sapping nature of the suburbs."

and

"A young Montreal jew discovers his vocation as a poet."

The previous, from Revolutionary Road by Richard Yates, I decided to give a chance because of the adulation all over the back cover by people like Kurt Vonnegut and Tennesee Williams. The latter book, The Favorite Game, I was curious enough to pick up strictly based on the name of it's author, Leonard Cohen.

REVOLUTIONARY ROAD by Richard Yates

"In our early youth we sit before the life that lies ahead of us like children sitting before the curtain in a theatre, in happy and tense anticipation of whatever is going to appear. Luckily we do not know what will really appear." Schopenhaur, from Of The Suffering of the World

Revolutionary Road opens with the rise of those very curtains, and the show is not pretty. Literally it is the premiere of a second-rate community theatre play somewhere in the woodsy suburbs of Connecticut that marks the beginning of what turns out to be the history of one very bad year in the life of the All-American family. April Wheeler is the star of the show, and her husband Frank is sitting in the audience, biting his knuckles for her. She appears in the first act as a shimmering stage beauty, but as the show wears on and starts to fall apart around her, Frank is horrified to watch her "dissolve and change into the graceless, suffering creature whose existence he tried every day of his life to deny". Things start to get bad after that.

Richard Yates´ parable of the destructive powers of suburbia seems so iconic that it's hard to believe that it was "lost" for so many years. Recently it has had a revival thanks to famous supporters like Vonnegut, as well as it's forewords's author Richard Ford, but for decades after it was first published in 1961 it was virtually forgotten and overlooked by all but a loyal fan base, mostly composed of other writers. In his forward Richard Ford describes invoking it's name as a kind of "secret handshake" amongst initiates.

The general consensus you get from quotes about and reviews of book now is "at least as good as The Great Gatsby", which is certainly the review Yates was shooting for when he wrote. Much is comparable in the two books, from the tone, the general leanness and lack of excess in the prose, the framing, and the use of what amounts to a small social anecdote to convey something sweeping and universally wrong with the American way of life.

The tone of Revolutionary Road is somewhat acidic and overwhelmingly negative, as if every aspect of modern life was corrupted and beyond repair, and yet the scary part is that nothing Yates describes seems artificial or forced. In fact, the whole story seems natural and, to an alarming extant, accurate.

The genius of the book is not that it is an indictment just of suburbia or mediocrity, but also of the innately American assumptions the people in it have about their intrinsic worth and potential. They have grown up believing, as most Americans do, that they could achieve greatness, that they were better than most. Confronting their essential mediocrity is what sends them spinning off into destruction. Revolutionary Road is not about how the suburbs can destroy those who are unaware, it's about people who know better and can still cannot escape.

It is in this way that I say the book is iconic. The story and the way it is spun seems to have informed, consciously or not, much of the pop cultural discourse about surburbia since it was published in 1961. You cannot watch a movie like American Beauty after reading Revolutionary Road and see it as anything but an homage to the book, and a dumbed-down or at least sugar-coated version at that. Road does not make heros or martyrs of it's rebels- April and Frank Wheeler think of themselves as rebels (they met in Greenwich village and had a love affair in Frank's grotty apartment when they were young and Frank fancied himself a "Jean-Paul-Satre-type"; April dreams of moving to Paris), but Yates portrays it as a false, self-important rebellion. And because Road was written before the hippie movement had taken hold, there are no counterculture cartoon characters around to tell everyone how to free their minds, unlike in American Beauty.

Well, actually, there is a character like that in ...Road, but in keeping with it's 1950's mythology framework, he is not a hippie guru but more of a "holy fool"- a paranoid psychotic who seems to be the only one in the book capable of speaking the truth. This fits in nicely with the intellectual, Freudian view of postwar America: that everything was so repressed that "blowing your top" was the only sane thing to do. This theme runs throughout Salinger- that craziness was the new word for sanity in 1950s America. In ...Road, the clinically insane character is the one that the Wheelers can identity with the most, but it the end he is the only one who can see through their hypocrisy. Neatly (as most everything is handled by Yates here), he is locked up for good after that by his repressed Mother, martyred for the truth that no one wanted to hear. Later, this kind of mythos of the iconoclast became a bit stale, but here in an early incarnation it is effective.

Ford suggests in the forward that you seek out the comedy in ..Road, and I tried. The humor I did find I find was black as can be. It's the kind of bleak, self depreciating humor of the suburbs later echoed in things like The Graduate, White Noise and The Ice Storm. It's the kind of stuff that makes me really excited to get back to the states. Genevieve, you want to move to Connecticut?

THE FAVORITE GAME by Leonard Cohen

Have you every heard the song "Brother with an Ego" by Cody Chestnut? It's lyrics are as follows-

"Sexy Bitches that I Fuck with my Big Black Penis/

Think that I'm a Motherfucking Musical Genius"

I don't think that Cody knew he was paraphrasing Leonard Cohen's main thesis from The Favorite Game when he wrote that song. Of course, Leonards phrase was slightly different, something like "Sexy shiksehs I shtup with my big Semitic schmuck/ Think that I'm a brilliant poetic little fuck". The Favorite Game is a laundry list of Cohen's early conquests, and a history of all the poems they inspired. The publishers and the author of the book's afterword would have you believe that this is no autobiography, but the similarities in the story and the age of the author make it difficult for me to think it is anything but.

The Favorite Game, written in 1963 before Cohen had achieved international fame, is the story of Lawrence Breaveman, a diminutive son of an affluent Montreal Jewish family. Lawrence is a fledgling poet with musical talent and an obsession with sex and spirituality. I don't think I need to recount Leonard Cohen's background.

As a novel, The Favorite Game lacks a lot in narrative arc and dramatic development, but as it is written by Leonard Cohen, there is a lot of beauty in the prose. Often, though, I found myself wishing the prose would get over it's own beauty, like I wished Laurence Breavman would get over himself.

It's also a little hard to have your narrator describe himself doing things like needlessly dissecting a frog, watching a man kill at cat and not stopping it, and hypnotizing and virtually raping a family friend and try to portray them as poetic or important. I could accept these things, along with his consistently poor treatment of women, if he ever just chalked it up to immaturity and ego. But throughout his tone is self-aggrandizing and somewhat pompous.

I liked the book better in it's third part when Cohen turns his gaze on Shell, who seems to be his favorite of the seven or so women that The Favorite Game is about. When Cohen brings his keen insight to someone other than Breavman, the result is a touching and complete portrayal of a human being.

This brings us to the main problem of the book- I can accept the fact that the words "jew" or "jewish" and "Montreal" are found on every page, but no mention of those wonderful bagels that put Montreal Jews on the map!

Leonard Cohen once famously said "The situation between men and women is irreparable". After reading The Favorite Game, you might be prompted so say, as I did, "No, Lenny, the situation between YOU and women is irreparable." I said it to a Bolivian man who just happened to be walking by, which was confusing for both of us.

"A young married couple struggles with the soul-sapping nature of the suburbs."

and

"A young Montreal jew discovers his vocation as a poet."

The previous, from Revolutionary Road by Richard Yates, I decided to give a chance because of the adulation all over the back cover by people like Kurt Vonnegut and Tennesee Williams. The latter book, The Favorite Game, I was curious enough to pick up strictly based on the name of it's author, Leonard Cohen.

REVOLUTIONARY ROAD by Richard Yates

"In our early youth we sit before the life that lies ahead of us like children sitting before the curtain in a theatre, in happy and tense anticipation of whatever is going to appear. Luckily we do not know what will really appear." Schopenhaur, from Of The Suffering of the World

Revolutionary Road opens with the rise of those very curtains, and the show is not pretty. Literally it is the premiere of a second-rate community theatre play somewhere in the woodsy suburbs of Connecticut that marks the beginning of what turns out to be the history of one very bad year in the life of the All-American family. April Wheeler is the star of the show, and her husband Frank is sitting in the audience, biting his knuckles for her. She appears in the first act as a shimmering stage beauty, but as the show wears on and starts to fall apart around her, Frank is horrified to watch her "dissolve and change into the graceless, suffering creature whose existence he tried every day of his life to deny". Things start to get bad after that.

Richard Yates´ parable of the destructive powers of suburbia seems so iconic that it's hard to believe that it was "lost" for so many years. Recently it has had a revival thanks to famous supporters like Vonnegut, as well as it's forewords's author Richard Ford, but for decades after it was first published in 1961 it was virtually forgotten and overlooked by all but a loyal fan base, mostly composed of other writers. In his forward Richard Ford describes invoking it's name as a kind of "secret handshake" amongst initiates.

The general consensus you get from quotes about and reviews of book now is "at least as good as The Great Gatsby", which is certainly the review Yates was shooting for when he wrote. Much is comparable in the two books, from the tone, the general leanness and lack of excess in the prose, the framing, and the use of what amounts to a small social anecdote to convey something sweeping and universally wrong with the American way of life.

The tone of Revolutionary Road is somewhat acidic and overwhelmingly negative, as if every aspect of modern life was corrupted and beyond repair, and yet the scary part is that nothing Yates describes seems artificial or forced. In fact, the whole story seems natural and, to an alarming extant, accurate.

The genius of the book is not that it is an indictment just of suburbia or mediocrity, but also of the innately American assumptions the people in it have about their intrinsic worth and potential. They have grown up believing, as most Americans do, that they could achieve greatness, that they were better than most. Confronting their essential mediocrity is what sends them spinning off into destruction. Revolutionary Road is not about how the suburbs can destroy those who are unaware, it's about people who know better and can still cannot escape.

It is in this way that I say the book is iconic. The story and the way it is spun seems to have informed, consciously or not, much of the pop cultural discourse about surburbia since it was published in 1961. You cannot watch a movie like American Beauty after reading Revolutionary Road and see it as anything but an homage to the book, and a dumbed-down or at least sugar-coated version at that. Road does not make heros or martyrs of it's rebels- April and Frank Wheeler think of themselves as rebels (they met in Greenwich village and had a love affair in Frank's grotty apartment when they were young and Frank fancied himself a "Jean-Paul-Satre-type"; April dreams of moving to Paris), but Yates portrays it as a false, self-important rebellion. And because Road was written before the hippie movement had taken hold, there are no counterculture cartoon characters around to tell everyone how to free their minds, unlike in American Beauty.

Well, actually, there is a character like that in ...Road, but in keeping with it's 1950's mythology framework, he is not a hippie guru but more of a "holy fool"- a paranoid psychotic who seems to be the only one in the book capable of speaking the truth. This fits in nicely with the intellectual, Freudian view of postwar America: that everything was so repressed that "blowing your top" was the only sane thing to do. This theme runs throughout Salinger- that craziness was the new word for sanity in 1950s America. In ...Road, the clinically insane character is the one that the Wheelers can identity with the most, but it the end he is the only one who can see through their hypocrisy. Neatly (as most everything is handled by Yates here), he is locked up for good after that by his repressed Mother, martyred for the truth that no one wanted to hear. Later, this kind of mythos of the iconoclast became a bit stale, but here in an early incarnation it is effective.

Ford suggests in the forward that you seek out the comedy in ..Road, and I tried. The humor I did find I find was black as can be. It's the kind of bleak, self depreciating humor of the suburbs later echoed in things like The Graduate, White Noise and The Ice Storm. It's the kind of stuff that makes me really excited to get back to the states. Genevieve, you want to move to Connecticut?

THE FAVORITE GAME by Leonard Cohen

Have you every heard the song "Brother with an Ego" by Cody Chestnut? It's lyrics are as follows-

"Sexy Bitches that I Fuck with my Big Black Penis/

Think that I'm a Motherfucking Musical Genius"

I don't think that Cody knew he was paraphrasing Leonard Cohen's main thesis from The Favorite Game when he wrote that song. Of course, Leonards phrase was slightly different, something like "Sexy shiksehs I shtup with my big Semitic schmuck/ Think that I'm a brilliant poetic little fuck". The Favorite Game is a laundry list of Cohen's early conquests, and a history of all the poems they inspired. The publishers and the author of the book's afterword would have you believe that this is no autobiography, but the similarities in the story and the age of the author make it difficult for me to think it is anything but.

The Favorite Game, written in 1963 before Cohen had achieved international fame, is the story of Lawrence Breaveman, a diminutive son of an affluent Montreal Jewish family. Lawrence is a fledgling poet with musical talent and an obsession with sex and spirituality. I don't think I need to recount Leonard Cohen's background.

As a novel, The Favorite Game lacks a lot in narrative arc and dramatic development, but as it is written by Leonard Cohen, there is a lot of beauty in the prose. Often, though, I found myself wishing the prose would get over it's own beauty, like I wished Laurence Breavman would get over himself.

It's also a little hard to have your narrator describe himself doing things like needlessly dissecting a frog, watching a man kill at cat and not stopping it, and hypnotizing and virtually raping a family friend and try to portray them as poetic or important. I could accept these things, along with his consistently poor treatment of women, if he ever just chalked it up to immaturity and ego. But throughout his tone is self-aggrandizing and somewhat pompous.

I liked the book better in it's third part when Cohen turns his gaze on Shell, who seems to be his favorite of the seven or so women that The Favorite Game is about. When Cohen brings his keen insight to someone other than Breavman, the result is a touching and complete portrayal of a human being.

This brings us to the main problem of the book- I can accept the fact that the words "jew" or "jewish" and "Montreal" are found on every page, but no mention of those wonderful bagels that put Montreal Jews on the map!

Leonard Cohen once famously said "The situation between men and women is irreparable". After reading The Favorite Game, you might be prompted so say, as I did, "No, Lenny, the situation between YOU and women is irreparable." I said it to a Bolivian man who just happened to be walking by, which was confusing for both of us.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)